Could it really be New Year’s Eve without looking back, taking in what the year has been, before taking a break, pouring the champagne, and welcoming a new year? Not for me! “Regrets, I’ve had a few . . . but then again, too few to mention . . .”

Okay, okay! I will mention maybe a few. In the form of some errata. But forgive a few wonderful memories too.

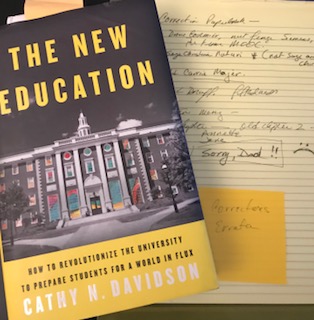

First the memories: I’m purposely leaving national politics aside to focus on what has been an amazing Fall, beginning with the Sept 5 publication of The New Education: How To Revolutionize the University to Prepare Students for a World in Flux (Basic Books). New Education is the distillation of several decades of research, teaching, interviews with hundreds (no, it must be thousands) of faculty members of every age and in every field, of equally many administrators and policy makers, of technology designers, and, of course with thousands (tens of thousands?) of students. At a dispiriting time, it has been inspiring and humbling to meet people working dedicated to redesigning higher education on behalf of a more equitable future.

Of course I want students to find great jobs when they graduate–but that requires not just changed education but massive social change. Deflated wages, contingent jobs, the tech sector unregulated and monopolistic and unfair: we need to educate ourselves in order to demand changes in all of these areas. Rampant profits for the .1% and strangulated economies for everyone else are a social problem–no matter how relevant your education is. We need to be educated to create a better society in which income equality, participation, and democracy are core values–for business too.

***

The New Education went through many rounds of revision, the entire book rewritten top to bottom four times, with my demanding and wonderful editor (thank you, Dan Gerstle) always insisting that I make my points as clearly and passionately as possible for a reader who might not ever read another book on higher education. That was my goal, while still being respectful of the abundant scholarship by specialists on higher education.

I aimed to write a higher education page turner. That may sound oxymoronic but my goal was to write a book that people read to the end, with exciting stories chosen from thousands of possible ones in order to move the narrative forward, provide new insights, represent different kinds of approaches and institutions and missions and goals. But always, first, the stories of transformation, stories that others could admire and model and emulate.

Another goal of the book: to highlight brilliance everywhere, not just the usual stories of the D-School at Stanford and the Media Lab at MIT but stories at your local, regional university, your liberal arts college, your community college where dedicated faculty and administrators and students are working hard, often without much support, to make change.

As I say early on, we have the models. Now we need the movement for higher education support and higher education transformation. We owe that to students today. They’ve had a raw deal.

***

It’s been thrilling that The New Education has been received so well. I hear from readers every single day–high school students and teachers and parents and principles as well as college and foundation presidents. Whenever I regret something I left out–whole chapters written and discarded–I remember who would have been excluded, as readers, had I opted to write a more scholarly and substantial (and longer) book.

***

A bit of personal history here (from the original Chapter One, omitted from the book): I have been reading and enacting alternative, engaged pedagogies my entire career . . .

I was an adjunct prof for three years after earning my PhD at an unusually young age. I taught at a number of Chicago-area liberal arts and community colleges, taught in both prison and mental health programs, and conducted a reading group for high-energy US and Russian physicists at the Fermi National Accelerator Lab. I thought part-time teaching at many institutions at a time would be lifelong (which is one reason why the horrific situation of adjunct profs has been a concern of mine for decades: in my 1993 American Studies Association Presidential Address I castigated a “profession that devours its young”: if we senior faculty were not fighting for full-time positions for new members of our profession, what would we fight for?) I finally landed a one-year visiting job “with the possibility of a permanent” position at St Bonaventure–and I was “fired” from it. Not technically. I simply wasn’t renewed, but it was a big deal: I organized a Woman’s Day on campus, including a panel on the various kinds of reproductive freedom and control. Ooops. That was controversial enough that editorials appeared about me in the local campus and town newspapers. I was told that Monday that my contract would not be renewed. (It was controversial enough that a saintly priest stepped in and, after I was let go, offered me a job co-teaching the first-ever women’s studies course to be taught in a Franciscan monastery. I came back a year later and we taught “Womanhood and the Franciscan Ideal,” the first–and the last–such venture. All my students were nuns and priests on their way to a PhD in Franciscan studies.)

But I digress . . .

***

Here’s a funny aside: at one of the first ever conferences held by the brand new National Women’s Studies Association, at the University of Connecticut, I stayed up all night talking about losing my first full-time job because of my activist, engaged, feminist pedagogy with a number of dear friends and suite mates, one of whom was Gloria Watkins. Most of you know her as “bell hooks.” She was as brilliant then, in her twenties, as she is now.

We’ve been teaching to transgress for a long time. . . .

OKAY! That’s all the Auld Lang Syne I can handle!

***

Regrets? Whenever one publishes a book, no matter how careful one has been, one discovers mistakes. People point them out to you. When you see them, fresh and glaring on the printed page, you cannot believe you could have made such an obvious, terrible error. But, alas! We all do make errors. (When I became editor of American Literature, the outgoing editor, Lou Budd, who had been at it for decades, very kindly told me that he had read every issue during his editorship, cover to cover, hoping to find one that had been printed without a single error. He had never once succeeded. What a gift to have him tell me that on my first day in the office!)

Errata:

If The New Education goes into a new edition, here are some errors I will correct when the book is printed in a new edition:

p. 81. The brilliant math teacher Derek Bruff has written me with very kind and generous words on my section about him, based on our interview and my reading of his work. He, rightly, takes umbrage at my using the phrase “mathematically gifted” and attributing it to him. He’s 100% right. When I go back and listen to the tape of our interview, I am not 100% positive but strongly suspect he used the word “adept,” not “gifted.” I misheard. I apologize. I’ll correct it in the next edition.

So what’s wrong with “gifted”? It has a terrible history and represents everything that I (and Prof Bruff) despise about a certain kind of false, pseudo-scientific magical thinking that pervades far too much education, preschool to graduate school. It as is if people are born with a “gift” when we know that there is no “math gene” and, to believe there is, defeats and undermines the whole point of engaged, active learning.

Everything Prof Bruff stands for is about teaching math to everyone, at every level, and not assuming math is somehow a “gift” you have but, rather, is a skill, methods, ideas, practices that you learn. I could not agree more! I don’t think he has ever used the word “gifted” in his own wonderful blog Agile Learning or his writings on pedagogy, for example.

In the original version of my chapter (this chapter, like all, went through many copy edits), that sentence comes after, not before, the paragraph about how Prof Bruff works to reach all his students, the 10 percent who come in already proficient in math, the ten percent struggling to learn, and the eighty percent who are lost and alienated and think they hate math. Prof Bruff turns them around, using engaged pedagogical methods. I’m honored that he let me interview him and regret that the “G word” somehow entered in.

p. 123. The term MOOC was originally coined by the Canadian learning innovator Dave Cormier, not by his friend, the Canadian innovator of constructivist education, George Siemens. I know that history well. I edited that chapter too many times and somehow this happened. So sorry. As an honorary Canadian (I spent over 20 years off and on in Canada), I’m especially abashed (and bewildered) that I messed that up. Again, it will be corrected in the next edition.

p. 275. My niece! I am so sorry fabulous Sage Christine Notari that you became two people in a bit of careless proofreading . . . with a name spelled wrong to boot. Egads.

p. 276. How did I leave out the name of my publicist, Carrie Majer?

And the big one: all the friends, loved ones, scholars, and teachers who were left out when, near the end, in a final massive copy edit, we decided to dump the original Chapter One, a personal chapter about my own life as a student and then as a teacher, and all of the individuals–all those friends, loved, ones, scholars, teachers–who have indelibly shaped my life as an educator. It was not an effective way to engage the reader so, very late, we just chucked it, 100 pages, my personal educational story, and many references to key figures who influenced me personally and pedagogically.

“Regrets, I have more than a few” about some lost voices from this ur-chapter. There was a section on the fearless and brilliant administrator and scholar and feminist Annette Kolodny. Annette as unbelievably kind to me at the very beginning, when I was adjuncting, when I lost the job at Bonaventure. I do not remember but I suspect she may have been one of the suitemates with bell hooks at that early NWSA. She also waged a fearless (and successful) battle at the University of New Hampshire, over misogyny and anti-Semitism. She’s a hero.

Prof and Dean Annette Kolodny also wrote one of the classic works on higher education reform, Failing the Future: A Dean Looks at Higher Education in the Twenty-first Century. ( Duke University Press, 1998).

There was another section in the former Chapter One on Jane Tompkins, yet another fearless teacher and the author of the powerful and influential A Life in School: What the Teacher Learned (Perseus, 1998). Also indispensable. Many others were left out of that deleted chapter but I feel, worse, the loss of Annette and Jane.

And my Dad…. He once had most of an opening chapter, now gets a skimpy line or two at the back, in the Acknowledgments. Sorry, Dad. Love you! So let me tell your story here . . .

The New Education originally began with a chapter tracing my father’s life, as the son of Italian immigrants. His own father’s story is quite mysterious; my grandfather, Pietro Notari, had an elite secondary education in his native Florence, was matriculated and had begun university studies then suddenly, inexplicably, left for America. His background was highly unusual for his era but he died with his secret in tact, never telling why he left Florence (the only son of an only son for nine generations: he broke his parents’ heart when he left–the only part of the story we were ever told). He came to America right before World War I. He joined the Navy and was a lifelong patriot but also an ardent advocate for civil rights and justice. He owned a small tavern/pub/restaurant under the L tracks in Chicago, an Italian and Mexican restaurant in the German and Swedish area of Chicago. During the Depression, his business partner was African American, not exactly typical either. And because my grandfather was learned, and carried from Italy old family volumes of Aristotle, Augustine, and Dante, his tavern–Pete’s Place–was inexplicably populated by professors from Chicago-area universities. He held an annual Bocci tournament behind the tavern. Only recently, did I learn that almost no one who played in Pete’s annual Bocci tournament was Italian. Most were professors of Italian. Perhaps that is why I went on to become a prof myself.

But it is my Dad’s story that once began my book. I would never have gone to college without my father fighting for me, with my entire life history of getting kicked out of one school after another: 1st grade, 6th grade, 10 th grade, 11th grade, 12th grade (twice). My father fought for my education because he believes profoundly in the importance of higher education. I regret losing that story even though my editor was right that it was distracting from the actual message of the book.

My father, Paul Celestino Notari, was not a great high school student, he insists. His father wanted him to go into the family restaurant business. But, at 17, Dad signed up for the Navy, like his immigrant father before him, and was determined to fight for democracy and world peace. He took the famous and notoriously difficult Eddy Test and aced it, scoring in the top 1%. His life changed. He was immediately put into a special engineering corps, stationed with Marines on Peleliu after the Japanese had officially surrendered but while there were still Japanese holdouts on the island. (Yes, this is a story I and my siblings heard many times while growing up).

Here’s the part relevant to The New Education: America rewarded my father, and others who fought in WWII with a massive new investment in higher education. He would go on to earn a bachelor’s degree on the GI Bill . He began a career as an engineer in the exciting new field of microwaves and transistors at Motorola. Later, he earned an MBA, and moved into water and then renewable energy. Now 91, he continues to publish a monthly newsletter for scientists and interested others focusing on climate change, policy, and politics.

The GI Bill (The Service Man’s Readiustment Act of 1944) changed his life. The GI Bill changed America. Under Lyndon Johnson, the Great Society also prospered with the 1965 Higher Education Act. With the election of Ronald Reagan as Governor of California, that national investment in higher education took a different turn. Governor Reagan “took on” the University of California, made reducing corporate tax and the graduated income tax a Republic rallying cry, and then put those policies and principles into effect during his Presidency and the so-called “Reagan Revolution.” If students today pay high tuition at most of our public universities, if they have crowded classrooms and if over half of their courses are taught by adjunct professors with no hope of fair wages or job security and no say in the educational direction of their institutions, all of that is a direct legacy of a half century war on higher education.

…Which is to say a war on our future, and the future of our youth.

That is why I wrote The New Education: as a battle cry on behalf of higher education. In another edition, mistakes will be corrected, of course, but the long, personal, missing first chapter was sacrificed to a better narrative. Sorry, Dad! I would not be telling my story if it were not for yours. I’m sorry I wasn’t able to tell it in this book–but I know that you champion higher education and the purpose of learning and preparation for a complex future as much as I do. Thank you for that.

And here is my New Year’s Resolution: to fight even harder for a fair, better higher education. Fight, fight, fight!

Thank you, everyone, for everything you do to contribute to the future of higher education. Between January and June, I’ll be on the road again, with eighteen separate events, beginning on Jan 4 on a Presidential Panel at the Modern Language Association with Angela Davis, Judith Butler, ACLU’s Anthony Romero, and Mayan philosopher and activist Juan Intzin Lopez. My talk is “Schooled” and it is tough–and will include an interactive audience community-building radical pedagogy exercise. Of course. Fight, fight, fight! Never quit. Never give up.

If I’m in your area during one of my upcoming visits, please come up and introduce yourself. (Here’s the book tour schedule for Spring 2018: https://www.cathydavidson.com/home/speaking/ )

We have our work cut out for us in 2018. Together, we can do this!